My first Google Cardboard experience was InMind, a VR experience designed to give the viewer an inside look at the brain. I selected this title because I was really excited to have a VR experience in the context of the human body, to have greater understanding into what our brains look like. What I found was something else entirely.

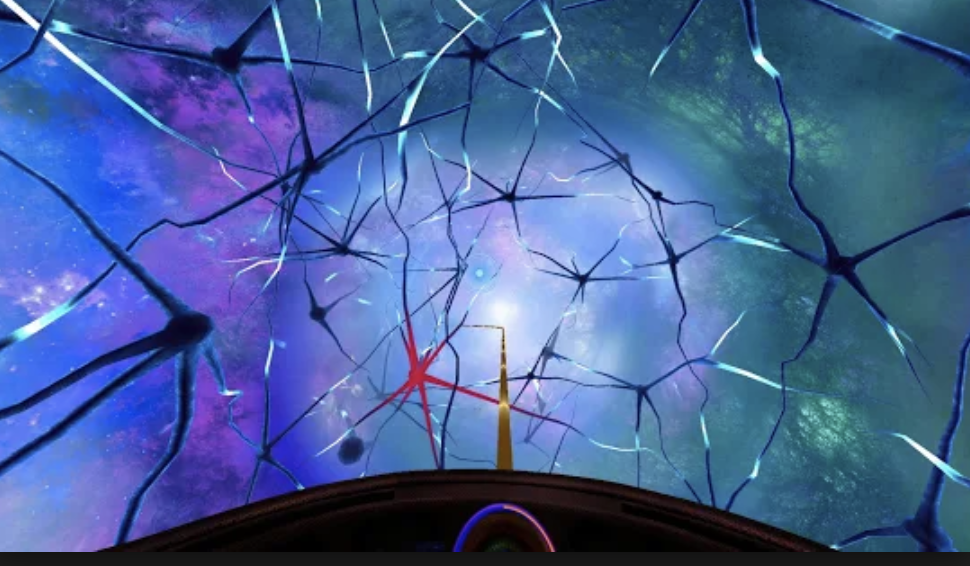

The experience began with an introduction in which the viewer is referred to as “Human.” The only other character in this experience was a robot narrator who speaks in a very patronizing manner to the viewer. The robot frames the narrative as “we are going to look into the brain of a patient who has depression” and the viewer is launched into what is evidently a game in which they must focus on the red neurons of the brain and turn them back to “normal” to “help” the patient. The ridiculous oversimplification of mental health aside, I do not feel that InMind achieves its goal of giving the viewer an immersive experience into the human brain.

First, the interaction is too slow. Feedback is given in the form of a circle becoming fully shaded when you concentrate on it. However, it takes too long for the circle to become full and thus, for the red neuron to change. It brought to mind what Chris Crawford says on interaction in his book “Interactive Storytelling,” that it must have speed. Furthermore, the interaction was slow in the sense that once you changed a few neurons, nothing seemed to happen. I grew bored. There seemed to be no progression in the narrative and when there finally was, it was merely a sentence or two from the robot who gave a feeble “keep going” message. Because there was such a focus on the red neurons, a pointless focus, I don’t think the viewer was necessarily observing the whole brain and all its synapses of activity. Sure, the environment was pretty, but it didn’t feel immersive. Perhaps that is because the game did not take full advantage of designing for VR since the rollercoaster through the brain only moved forward, not giving the viewer the chance to explore. Furthermore, I felt detached as a player. Perhaps, the game would have felt more immersive if there was more effort put into personalizing it. For instance, instead of being called “Human,” you could be called by your real name or a name you created.

Though the whole experience lasted only four minutes, it felt much longer. In this VR mind, I was bored out of my mind. The ending was just as dull as the progression: “congrats Human on not dying. Now download these other apps,” or something along those lines. I wouldn’t say that this was a waste of time though because it made me realize how important it is to have progression through a VR experience, a clear narrative if you will, and that there is attention given to how much feedback given to the viewer in this narrative and how fast the feedback takes.